Book of Mormon

| Book of Mormon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Information | |

| Religion | Latter Day Saint movement |

| Language | English |

| Period | 19th century |

| Chapters | |

| Full text | |

The Book of Mormon is a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, first published in 1830 by Joseph Smith as The Book of Mormon: An Account Written by the Hand of Mormon upon Plates Taken from the Plates of Nephi.[1][2]

The book is one of the earliest and most well-known unique writings of the Latter Day Saint movement. The denominations of the Latter Day Saint movement typically regard the text primarily as scripture (sometimes as one of four standard works) and secondarily as a record of God's dealings with ancient inhabitants of the Americas.[3] The majority of Latter Day Saints believe the book to be a record of real-world history, with Latter Day Saint denominations viewing it variously as an inspired record of scripture to the linchpin or "keystone" of their religion.[4][5] Independent archaeological, historical, and scientific communities have discovered little evidence to support the existence of the civilizations described therein.[6] Characteristics of the language and content point toward a nineteenth-century origin of the Book of Mormon. Various academics and apologetic organizations connected to the Latter Day Saint movement nevertheless argue that the book is an authentic account of the pre-Columbian exchange world.

The Book of Mormon has a number of doctrinal discussions on subjects such as the fall of Adam and Eve,[7] the nature of the Christian atonement,[8] eschatology, agency, priesthood authority, redemption from physical and spiritual death,[9] the nature and conduct of baptism, the age of accountability, the purpose and practice of communion, personalized revelation, economic justice, the anthropomorphic and personal nature of God, the nature of spirits and angels, and the organization of the latter day church. The pivotal event of the book is an appearance of Jesus Christ in the Americas shortly after his resurrection.[10] Common teachings of the Latter Day Saint movement hold that the Book of Mormon fulfills numerous biblical prophecies by ending a global apostasy and signaling a restoration of Christian gospel.

The Book of Mormon is divided into smaller books — which are usually titled after individuals named as primary authors — and in most versions, is divided into chapters and verses.[11] Its English text imitates the style of the King James Version of the Bible.[11] The Book of Mormon has been fully or partially translated into at least 112 languages.[12]

Origin

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Book of Mormon |

|---|

|

According to Smith's account and the book's narrative, the Book was originally engraved in otherwise unknown characters on golden plates by ancient prophets; the last prophet to contribute to the book, Moroni, had buried it in what is present-day Manchester, New York and then appeared in a vision to Smith in 1827, revealing the location of the plates and instructing him to translate the plates into English.[13][14] The more widely accepted view is that Smith authored the Book, drawing on material and ideas from his contemporary 19th-century environment, rather than translating an ancient record.[15][16]

Conceptual emergence

[edit]According to Joseph Smith, in 1823, when he was seventeen years old, an angel of God named Moroni appeared to him and said that a collection of ancient writings was buried in a nearby hill in present-day Wayne County, New York, engraved on golden plates by ancient prophets.[17][18] The writings were said to describe a people whom God had led from Jerusalem to the Western hemisphere 600 years before Jesus's birth.[14] Smith said this vision occurred on the evening of September 21, 1823, and that on the following day, via divine guidance, he located the burial location of the plates on this hill and was instructed by Moroni to meet him at the same hill on September 22 of the following year to receive further instructions, which repeated annually for the next three years.[19][20] Smith told his entire immediate family about this angelic encounter by the next night, and his brother William reported that the family "believed all he [Joseph Smith] said" about the angel and plates.[21]

Smith and his family reminisced that as part of what Smith believed was angelic instruction, Moroni provided Smith with a "brief sketch" of the "origin, progress, civilization, laws, governments ... righteousness and iniquity" of the "aboriginal inhabitants of the country" (referring to the Nephites and Lamanites who figure in the Book of Mormon's primary narrative). Smith sometimes shared what he said he had learned through such angelic encounters with his family as well.[22]

In Smith's account, Moroni allowed him, accompanied by his wife Emma Hale Smith, to take the plates on September 22, 1827, four years after his initial visit to the hill, and directed him to translate them into English.[23][24] Smith said the angel Moroni strictly instructed him to not let anyone else see the plates without divine permission.[25] Neighbors, some of whom had collaborated with Smith in earlier treasure-hunting enterprises, tried several times to steal the plates from Smith while he and his family guarded them.[26][27]

Dictation

[edit]As Smith and contemporaries reported, the English manuscript of the Book of Mormon was produced as scribes[28] wrote down Smith's dictation in multiple sessions between 1828 and 1829.[29][30] The dictation of the extant Book of Mormon was completed in 1829 in between 53 and 74 working days.[31][32]

Descriptions of the way in which Smith dictated the Book of Mormon vary. Smith himself called the Book of Mormon a translated work, but in public he generally described the process itself only in vague terms, saying he translated by a miraculous gift from God.[33] According to some accounts from his family and friends at the time, early on, Smith copied characters off the plates as part of a process of learning to translate an initial corpus.[34] For the majority of the process, Smith dictated the text by voicing strings of words which a scribe would write down; after the scribe confirmed they had finished writing, Smith would continue.[35]

Many accounts describe Smith dictating by reading a text as it appeared either on seer stones he already possessed or on a set of spectacles that accompanied the plates, prepared by the Lord for the purpose of translating.[36] The spectacles, often called the "Nephite interpreters," or the "Urim and Thummim," after the biblical divination stones, were described as two clear seer stones which Smith said he could look through in order to translate, bound together by a metal rim and attached to a breastplate.[37] Beginning around 1832, both the interpreters and Smith's own seer stone were at times referred to as the "Urim and Thummim", and Smith sometimes used the term interchangeably with "spectacles".[38] Emma Smith's and David Whitmer's accounts describe Smith using the interpreters while dictating for Martin Harris's scribing and switching to only using his seer stone(s) in subsequent translation.[39] Religious studies scholar Grant Hardy summarizes Smith's known dictation process as follows: "Smith looked at a seer stone placed in his hat and then dictated the text of the Book of Mormon to scribes".[40][41] Early on, Smith sometimes separated himself from his scribe with a blanket between them, as he did while Martin Harris, a neighbor, scribed his dictation in 1828.[42][43] At other points in the process, such as when Oliver Cowdery or Emma Smith scribed, the plates were left covered up but in the open.[44] During some dictation sessions the plates were entirely absent.[45][46]

In 1828, while scribing for Smith, Harris, at the prompting of his wife Lucy Harris, repeatedly asked Smith to loan him the manuscript pages of the dictation thus far. Smith reluctantly acceded to Harris's requests. Within weeks, Harris lost the manuscript, which was most likely stolen by a member of his extended family.[47] After the loss, Smith recorded that he lost the ability to translate and that Moroni had taken back the plates to be returned only after Smith repented.[48][49][39] Smith later stated that God allowed him to resume translation, but directed that he begin where he left off (in what is now called the Book of Mosiah), without retranslating what had been in the lost manuscript.[50]

Smith recommenced some Book of Mormon dictation between September 1828 and April 1829 with his wife Emma Smith scribing with occasional help from his brother Samuel Smith, though transcription accomplished was limited. In April 1829, Oliver Cowdery met Smith and, believing Smith's account of the plates, began scribing for Smith in what became a "burst of rapid-fire translation".[51] In May, Joseph and Emma Smith along with Cowdery moved in with the Whitmer family, sympathetic neighbors, in an effort to avoid interruptions as they proceeded with producing the manuscript.[52]

While living with the Whitmers, Smith said he received permission to allow eleven specific others to see the uncovered golden plates and, in some cases, handle them.[53] Their written testimonies are known as the Testimony of Three Witnesses, who described seeing the plates in a visionary encounter with an angel, and the Testimony of Eight Witnesses, who described handling the plates as displayed by Smith. Statements signed by them have been published in most editions of the Book of Mormon.[54] In addition to Smith and these eleven, several others described encountering the plates by holding or moving them wrapped in cloth, although without seeing the plates themselves.[55][56] Their accounts of the plates' appearance tend to describe a golden-colored compilation of thin metal sheets (the "plates") bound together by wires in the shape of a book.[57]

The manuscript was completed in June 1829.[31] E. B. Grandin published the Book of Mormon in Palmyra, New York, and it went on sale in his bookstore on March 26, 1830.[58] Smith said he returned the plates to Moroni upon the publication of the book.[59]

Views on composition

[edit]

Multiple theories of naturalistic composition have been proposed.[15] In the twenty-first century, leading naturalistic interpretations of Book of Mormon origins hold that Smith authored it himself, whether consciously or subconsciously, and simultaneously sincerely believed the Book of Mormon was an authentic sacred history.[60]

Most adherents of the Latter Day Saint movement consider the Book of Mormon an authentic historical record, translated by Smith from actual ancient plates through divine revelation. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), the largest Latter Day Saint denomination, maintains this as its official position.[61]

Methods

[edit]The Book of Mormon as a written text is the transcription of what scholars Grant Hardy and William L. Davis call an "extended oral performance", one which Davis considers "comparable in length and magnitude to the classic oral epics, such as Homer's Iliad and Odyssey".[62][63] Eyewitnesses said Smith never referred to notes or other documents while dictating,[64] and Smith's followers and those close to him insisted he lacked the writing and narrative skills necessary to consciously produce a text like the Book of Mormon.[65] Some naturalistic interpretations have therefore compared Smith's dictation to automatic writing arising from the subconscious.[15] However, Ann Taves considers this description problematic for overemphasizing "lack of control" when historical and comparative study instead suggests Smith "had a highly focused awareness" and "a considerable degree of control over the experience" of dictation.[66]

Independent scholar William L. Davis posits that after believing he had encountered an angel in 1823, Smith "carefully developed his ideas about the narratives" of the Book of Mormon for several years by making outlines, whether mental or on private notes, until he began dictating in 1828.[67] Smith's oral recitations about Nephites to his family could have been an opportunity to work out ideas and practice oratory, and he received some formal education as a lay Methodist exhorter.[68] In this interpretation, Smith believed the dictation he produced reflected an ancient history, but he assembled the narrative in his own words.[69]

Inspirations

[edit]Early observers, presuming Smith incapable of writing something as long or as complex as the Book of Mormon, often searched for a possible source he might have plagiarized.[70] In the nineteenth century, a popular hypothesis was that Smith collaborated with Sidney Rigdon to plagiarize an unpublished manuscript written by Solomon Spalding and turn into the Book of Mormon.[71] Historians have considered the Spalding manuscript source hypothesis debunked since 1945, when Fawn M. Brodie thoroughly disproved it in her critical biography of Smith.[72]

Historians since the early twentieth century have suggested Smith was inspired by View of the Hebrews, an 1823 book which propounded the Hebraic Indian theory, since both associate American Indians with ancient Israel and describe clashes between two dualistically opposed civilizations (View as speculation about American Indian history and the Book of Mormon as its narrative).[73][74] Whether or not View influenced the Book of Mormon is the subject of debate.[75] A pseudo-anthropological treatise, View presented allegedly empirical evidence in support of its hypothesis. The Book of Mormon is written as a narrative, and Christian themes predominate rather than supposedly Indigenous parallels.[76] Additionally, while View supposes that Indigenous American peoples descended from the Ten Lost Tribes, the Book of Mormon actively rejects the hypothesis; the peoples in its narrative have an "ancient Hebrew" origin but do not descend from the lost tribes. The book ultimately heavily revises, rather than borrows, the Hebraic Indian theory.[77]

The Book of Mormon may creatively reconfigure, without plagiarizing, parts of the popular 1678 Christian allegory Pilgrim's Progress written by John Bunyan. For example, the martyr narrative of Abinadi in the Book of Mormon shares a complex matrix of descriptive language with Faithful's martyr narrative in Progress. Some other Book of Mormon narratives, such as the dream Lehi has in the book's opening, also resemble creative reworkings of Progress story arcs as well as elements of other works by Bunyan, such as The Holy War and Grace Abounding.[63]

Historical scholarship also suggests it is plausible for Smith to have produced the Book of Mormon himself, based on his knowledge of the Bible and enabled by a democratizing religious culture.[70]

Content

[edit]

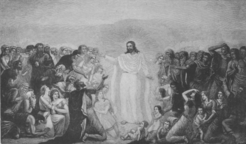

(Image from the U.S. Library of Congress Rare Book and Special Collections Division)

Presentation

[edit]The style of the Book of Mormon's English text resembles that of the King James Version of the Bible.[78] Novelist Jane Barnes considered the book "difficult to read",[79] and according to religious studies scholar Grant Hardy, the language is an "awkward, repetitious form of English" with a "nonmainstream literary aesthetic".[80] Narratively and structurally, the book is complex, with multiple arcs that diverge and converge in the story while contributing to the book's overarching plot and themes.[81] Historian Daniel Walker Howe concluded in his own appraisal that the Book of Mormon "is a powerful epic written on a grand scale" and "should rank among the great achievements of American literature".[82]

The Book of Mormon presents its text through multiple narrators explicitly identified as figures within the book's own narrative. Narrators describe reading, redacting, writing, and exchanging records.[83] The book also embeds sermons, given by figures from the narrative, throughout the text, and these internal orations make up just over 40 percent of the Book of Mormon.[84] Periodically, the book's primary narrators reflexively describe themselves creating the book in a move that is "almost postmodern" in its self-consciousness.[85] Historian Laurie Maffly-Kipp explains that "the mechanics of editing and transmitting thereby become an important feature of the text".[86] Barnes calls the Book of Mormon a "scripture about writing and its influence in a post-modern world of texts" and "a statement about different voices, and possibly the problem of voice, in sacred literature".[87]

Organization

[edit]The Book of Mormon is organized as a compilation of smaller books, each named after its main named narrator or a prominent leader, beginning with the First Book of Nephi (1 Nephi) and ending with the Book of Moroni.[88]

The book's sequence is primarily chronological based on the narrative content of the book. Exceptions include the Words of Mormon and the Book of Ether.[89] The Words of Mormon contains editorial commentary by Mormon. The Book of Ether is presented as the narrative of an earlier group of people who had come to the American continent before the immigration described in 1 Nephi. First Nephi through Omni are written in first-person narrative, as are Mormon and Moroni. The remainder of the Book of Mormon is written in third-person historical narrative, said to be compiled and abridged by Mormon (with Moroni abridging the Book of Ether and writing the latter part of Mormon and the Book of Moroni).

Most modern editions of the book have been divided into chapters and verses.[11] Most editions of the book also contain supplementary material, including the "Testimony of Three Witnesses" and the "Testimony of Eight Witnesses" which appeared in the original 1830 edition and every official Latter-day Saint edition thereafter.[54]

Narrative

[edit]The books from First Nephi to Omni are described as being from "the small plates of Nephi".[90] This account begins in ancient Jerusalem around 600 BC, telling the story of a man named Lehi, his family, and several others as they are led by God from Jerusalem shortly before the fall of that city to the Babylonians. The book describes their journey across the Arabian peninsula, and then to a "promised land", presumably an unspecified location in the Americas, by ship.[91] These books recount the group's dealings from approximately 600 BC to about 130 BC, during which time the community grows and splits into two main groups, called Nephites and Lamanites, that frequently war with each other throughout the rest of the narrative.[92]

Following this section is the Words of Mormon, a small book that introduces Mormon, the principal narrator for the remainder of the text.[90] The narration describes the proceeding content (Book of Mosiah through to chapter 7 of the internal Book of Mormon) as being Mormon's abridgment of "the large plates of Nephi", existing records that detailed the people's history up to Mormon's own life.[93] Part of this portion is the Book of Third Nephi, which describes a visit by Jesus to the people of the Book of Mormon sometime after his resurrection and ascension; historian John Turner calls this episode "the climax of the entire scripture".[94] After this visit, the Nephites and Lamanites unite in a harmonious, peaceful society which endures for several generations before breaking into warring factions again,[95] and in this conflict the Nephites are destroyed while the Lamanites emerge victorious.[96] In the narrative, Mormon, a Nephite, lives during this period of war, and he dies before finishing his book.[97] His son Moroni takes over as narrator, describing himself taking his father's record into his charge and finishing its writing.[98]

Before the very end of the book, Moroni describes making an abridgment (called the Book of Ether) of a record from a much earlier people.[99] There is a subsequent subplot describing a group of families who God leads away from the Tower of Babel after it falls.[95] Led by a man named Jared and his brother, described as a prophet of God, these Jaredites travel to the "promised land" and establish a society there. After successive violent reversals between rival monarchs and faction, their society collapses around the time that Lehi's family arrive in the promised land further south.[100]

The narrative returns to Moroni's present (Book of Moroni) in which he transcribes a few short documents, meditates on and addresses the book's audience, finishes the record, and buries the plates upon which they are narrated to be inscribed upon, before implicitly dying as his father did, in what allegedly would have been the early 400s CE.[101][102]

Teachings

[edit]Jesus

[edit]On its title page, the Book of Mormon describes its central purpose as being the "convincing of the Jew and Gentile that Jesus is the Christ, the Eternal God, manifesting himself unto all nations."[103] Although much of the Book of Mormon's internal chronology takes place prior to the birth of Jesus, prophets in the book frequently see him in vision and preach about him, and the people in the narrative worship Jesus as "pre-Christian Christians."[104][94] For example, the book's first narrator Nephi describes having a vision of the birth, ministry, and death of Jesus, said to have taken place nearly 600 years prior to Jesus' birth.[105] Late in the book, a narrator refers to converted peoples as "children of Christ".[106] By depicting ancient prophets and peoples as familiar with Jesus as a Savior, the Book of Mormon universalizes Christian salvation as being accessible across all time and places.[107][108] By implying that even more ancient peoples were familiar with Jesus Christ, the book presents a "polygenist Christian history" in which Christianity has multiple origins.[77]

In the climax of the book, Jesus visits some early inhabitants of the Americas after his resurrection in an extended bodily theophany.[10][94] During this ministry, he reiterates many teachings from the New Testament, re-emphasizes salvific baptism, and introduces the ritual consumption of bread and wine "in remembrance of [his] body", a teaching that became the basis for modern Latter-day Saints' "memorialist" view of their sacrament ordinance (analogous to communion).[109] Jesus's ministry in the Book of Mormon resembles his portrayal in the Gospel of John, as Jesus similarly teaches without parables and preaches faith and obedience as a central message.[110][111]

Barnes argues that the Book of Mormon depicts Jesus as a "revolutionary new character" different from that of the New Testament in a portrayal that is "constantly, subtly revising the Christian tradition".[87] According to historian John Turner, the Book of Mormon's depiction provides "a twist" on Christian trinitarianism, as Jesus in the Book of Mormon is distinct from God the Father—as he prays to God during a post-resurrection visit with the Nephites—while also emphasizing that Jesus and God have "divine unity," with other parts of the book calling Jesus "the Father and the Son".[112] Beliefs among the churches of the Latter Day Saint movement range between social trinitarianism (such as among Latter-day Saints)[113] and traditional trinitarianism (such as in Community of Christ).[114]

Plan of salvation

[edit]The Christian concept of God's plan of salvation for humanity is a frequently recurring theme of the Book of Mormon.[115] While the Bible does not directly outline a plan of salvation, the Book of Mormon explicitly refers to the concept thirty times, using a variety of terms such as plan of salvation, plan of happiness, and plan of redemption. The Book of Mormon's plan of salvation doctrine describes life as a probationary time for people to learn the gospel of Christ through revelation given to prophets and have the opportunity to choose whether or not to obey God. Jesus' atonement then makes repentance possible, enabling the righteous to enter a heavenly state after a final judgment.[116]

Although most of Christianity traditionally considers the fall of man a negative development for humanity,[117] the Book of Mormon instead portrays the fall as a foreordained step in God's plan of salvation, necessary to securing human agency, eventual righteousness,[116] and bodily joy through physical experience.[118] This positive interpretation of the Adam and Eve story contributes to the Book of Mormon's emphasis "on the importance of human freedom and responsibility" to choose salvation.[116]

Dialogic revelation

[edit]In the Book of Mormon, revelation from God typically manifests as a dialogue between God and persons, characterizing deity as an anthropomorphic being who hears prayers and provides direct answers to questions.[119] Multiple narratives in the book portray revelation as a dialogue in which petitioners and deity engage one another in a mutual exchange in which God's contributions originate from outside the mortal recipient.[120] The Book of Mormon also emphasizes regular prayer as a significant component of devotional life, depicting it as a central means through which such dialogic revelation can take place.[121] While the Old Testament of the Christian Bible links revelation specifically to prophetic authority, the Book of Mormon's portrayal democratizes the idea of revelation, depicting it as the right of every person. Figures such as Nephi and Ammon receive visions and revelatory direction prior to or without ever becoming prophets, and Laman and Lemuel are rebuked for hesitating to pray for revelation.[122] Also in contrast with traditional Christian conceptions of revelations is the Book of Mormon's broader range of revelatory content.[123] In the Book of Mormon, figures petition God for revelatory answers to doctrinal questions and ecclesiastical crises as well as for inspiration to guide hunts, military campaigns, and sociopolitical decisions.[124] The Book of Mormon depicts revelation as an active and sometimes laborious experience. For example, the Book of Mormon's Brother of Jared learns to act not merely as a petitioner with questions but moreover as an interlocutor with "a specific proposal" for God to consider as part of a guided process of miraculous assistance.[125]

Apocalyptic reversal and Indigenous or nonwhite liberation

[edit]The Book of Mormon's "eschatological content" lends to a "theology of Native and/or nonwhite liberation", in the words of American studies scholar Jared Hickman.[126] The Book of Mormon's narrative content includes prophecies describing how although Gentiles (generally interpreted as being whites of European descent) would conquer the Indigenous residents of the Americas (imagined in the Book of Mormon as being a remnant of descendants of the Lamanites), this conquest would only precede the Native Americans' revival and resurgence as a God-empowered people. The Book of Mormon narrative's prophecies envision a Christian eschaton in which Indigenous people are destined to rise up as the true leaders of the continent, manifesting in a new utopia to be called "Zion".[127] White Gentiles would have an opportunity to repent of their sins and join themselves to the Indigenous remnant,[128] but if white Gentile society fails to do so, the Book of Mormon's content foretells a future "apocalyptic reversal" in which Native Americans will destroy white American society and replace it with a godly, Zionic society.[129][130] This prophecy commanding whites to repent and become supporters of American Indians even bears "special authority as an utterance of Jesus" Christ himself during a messianic appearance at the book's climax.[126]

Furthermore, the Book of Mormon's "formal logic" criticizes the theological supports for racism and white supremacy prevalent in the antebellum United States by enacting a textual apocalypse.[126] The book's apparently white Nephite narrators fail to recognize and repent of their own sinful, hubristic prejudices against the seemingly darker-skinned Lamanites in the narrative. In their pride, the Nephites repeatedly backslide into producing oppressive social orders, such that the book's narrative performs a sustained critique of colonialist racism.[131] The book concludes with its own narrative implosion in which Lamanites suddenly succeed over and destroy Nephites in a literary turn seemingly designed to jar the average antebellum white American reader into recognizing the "utter inadequacy of his or her rac(ial)ist common sense".[126]

Religious significance

[edit]Early Mormonism

[edit]

Adherents of the early Latter Day Saint movement frequently read the Book of Mormon as a corroboration of and supplement to the Bible, persuaded by its resemblance to the King James Version's form and language. For these early readers, the Book of Mormon confirmed the Bible's scriptural veracity and resolved then-contemporary theological controversies the Bible did not seem to adequately address, such as the appropriate mode of baptism, the role of prayer, and the nature of the Christian atonement.[132] Early church administrative design also drew inspiration from the Book of Mormon. Oliver Cowdery and Joseph Smith, respectively, used the depiction of the Christian church in the Book of Mormon as a template for their Articles of the Church and Articles and Covenants of the Church.[133]

The Book of Mormon was also significant in the early movement as a sign, proving Joseph Smith's claimed prophetic calling, signalling the "restoration of all things", and ending what was believed to have been an apostasy from true Christianity.[134][135] Early Latter Day Saints tended to interpret the Book of Mormon through a millenarian lens and consequently believed the book portended Christ's imminent Second Coming.[136] And during the movement's first years, observers identified converts with the new scripture they propounded, nicknaming them "Mormons".[137]

Early Mormons also cultivated their own individual relationships with the Book of Mormon. Reading the book became an ordinary habit for some, and some would reference passages by page number in correspondence with friends and family. Historian Janiece Johnson explains that early converts' "depth of Book of Mormon usage is illustrated most thoroughly through intertextuality—the pervasive echoes, allusions, and expansions on the Book of Mormon text that appear in the early converts' own writings." Early Latter Day Saints alluded to Book of Mormon narratives, incorporated Book of Mormon turns of phrase into their writing styles, and even gave their children Book of Mormon names.[133]

Joseph Smith

[edit]Like many other early adherents of the Latter Day Saint movement, Smith referenced Book of Mormon scriptures in his preaching relatively infrequently and cited the Bible more often.[138] In 1832, Smith dictated a revelation that condemned the "whole church" for treating the Book of Mormon lightly, although even after doing so Smith still referenced the Book of Mormon less often than the Bible.[138] Nevertheless, in 1841 Joseph Smith characterized the Book of Mormon as "the most correct of any book on earth, and the keystone of [the] religion".[139] Although Smith quoted the book infrequently, he accepted the Book of Mormon narrative world as his own.[140]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

[edit]The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) accepts the Book of Mormon as one of the four sacred texts in its scriptural canon called the standard works.[141] Church leaders and publications have "strongly affirm[ed]" Smith's claims of the book's significance to the faith.[142] According to the church's "Articles of Faith"—a document written by Joseph Smith in 1842 and canonized by the church as scripture in 1880—members "believe the Bible to be the word of God as far as it is translated correctly," and they "believe the Book of Mormon to be the word of God," without qualification.[143][144] In their evangelism, Latter-day Saint leaders and missionaries have long emphasized the book's place in a causal chain which held that if the Book of Mormon was "verifiably true revelation of God," then it justified Smith's claims to prophetic authority to restore the New Testament church.[145]

Latter-day Saints have also long believed the Book of Mormon's contents confirm and fulfill biblical prophecies.[146] For example, "many Latter-day Saints" consider the biblical patriarch Jacob's description of his son Joseph as "a fruitful bough ... whose branches run over a wall" a prophecy of Lehi's posterity—described as descendants of Joseph—overflowing into the New World.[147] Latter-day Saints also believe the Bible prophesies of the Book of Mormon as an additional testament to God's dealings with humanity.[148][149]

In the 1980s, the church placed greater emphasis on the Book of Mormon as a central text of the faith.[150][151] In 1982, it added the subtitle "Another Testament of Jesus Christ" to its official editions of the Book of Mormon.[152][153] Ezra Taft Benson, the church's thirteenth president (1985–1994), especially emphasized the Book of Mormon.[142][154] Referencing Smith's 1832 revelation, Benson said the church remained under condemnation for treating the Book of Mormon lightly.[154]

Since the late 1980s, Latter-day Saint leaders have encouraged church members to read from the Book of Mormon daily, and in the twenty-first century, many Latter-day Saints use the book in private devotions and family worship.[143][155] Literary scholar Terryl Givens observes that for Latter-day Saints, the Book of Mormon is "the principal scriptural focus", a "cultural touchstone, and "absolutely central" to worship, including in weekly services, Sunday School, youth seminaries, and more.[156]

Approximately 90 to 95% of all Book of Mormon printings have been affiliated with the church.[157] As of October 2020, it has published more than 192 million copies of the Book of Mormon.[158]

Community of Christ

[edit]The Community of Christ (formerly the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints or RLDS Church) views the Book of Mormon as scripture which provides an additional witness of Jesus Christ in support of the Bible.[159] The Community of Christ publishes two versions of the book. The first is the Authorized Edition, first published by the then-RLDS Church in 1908, whose text is based on comparing the original printer's manuscript and the 1837 Second Edition (or "Kirtland Edition") of the Book of Mormon.[160] Its content is similar to the Latter-day Saint edition of the Book of Mormon, but the versification is different.[161] The Community of Christ also publishes a "New Authorized Version" (also called a "reader's edition"), first released in 1966, which attempts to modernize the language of the text by removing archaisms and standardizing punctuation.[162]

Use of the Book of Mormon varies among Community of Christ membership. The church describes it as scripture and includes references to the Book of Mormon in its official lectionary.[163] In 2010, representatives told the National Council of Churches that "the Book of Mormon is in our DNA".[159][164] The book remains a symbol of the denomination's belief in continuing revelation from God.[165] Nevertheless, its usage in North American congregations declined between the mid-twentieth and twenty-first centuries.[163] Community of Christ theologian Anthony Chvala-Smith describes the Book of Mormon as being akin to a "subordinate standard" relative to the Bible, giving the Bible priority over the Book of Mormon,[165] and the denomination does not emphasize the book as part of its self-conceived identity.[161] Book of Mormon use varies in what David Howlett calls "Mormon heritage regions": North America, Western Europe, and French Polynesia.[166] Outside these regions, where there are tens of thousands of members,[163] congregations almost never use the Book of Mormon in their worship,[166] and they may be entirely unfamiliar with it.[163] Some in Community of Christ remain interested in prioritizing the Book of Mormon in religious practice and have variously responded to these developments by leaving the denomination or by striving to re-emphasize the book.[167]

During this time, the Community of Christ moved away from emphasizing the Book of Mormon as an authentic record of a historical past. By the late-twentieth century, church president W. Grant McMurray made open the possibility the book was nonhistorical.[162] McMurray reiterated this ambivalence in 2001, reflecting, "The proper use of the Book of Mormon as sacred scripture has been under wide discussion in the 1970s and beyond, in part because of long-standing questions about its historical authenticity and in part because of perceived theological inadequacies, including matters of race and ethnicity."[168] When a resolution was submitted at the 2007 Community of Christ World Conference to "reaffirm the Book of Mormon as a divinely inspired record", church president Stephen M. Veazey ruled it out-of-order. He stated, "while the Church affirms the Book of Mormon as scripture, and makes it available for study and use in various languages, we do not attempt to mandate the degree of belief or use. This position is in keeping with our longstanding tradition that belief in the Book of Mormon is not to be used as a test of fellowship or membership in the church."[167]

Greater Latter Day Saint movement

[edit]Since the death of Joseph Smith in 1844, there have been approximately seventy different churches that have been part of the Latter Day Saint movement, fifty of which were extant as of 2012. Religious studies scholar Paul Gutjahr explains that "each of these sects developed its own special relationship with the Book of Mormon".[169] For example James Strang, who led a denomination in the nineteenth century, reenacted Smith's production of the Book of Mormon by claiming in the 1840s and 1850s to receive and translate new scriptures engraved on metal plates, which became the Voree Plates and the Book of the Law of the Lord.[170]

William Bickerton led another denomination, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (today called The Church of Jesus Christ), which accepted the Book of Mormon as scripture alongside the Bible although it did not canonize other Latter Day Saint religious texts like the Doctrine and Covenants and Pearl of Great Price.[171] The contemporary Church of Jesus Christ continues to consider the "Bible and Book of Mormon together" to be "the foundation of [their] faith and the building blocks of" their church.[172]

Nahua-Mexican Latter-day Saint Margarito Bautista believed the Book of Mormon told an Indigenous history of Mexico before European contact, and he identified himself as a "descendant of Father Lehi", a prophet in the Book of Mormon.[173] Bautista believed the Book of Mormon revealed that Indigenous Mexicans were a chosen remnant of biblical Israel and therefore had a sacred destiny to someday lead the church spiritually and the world politically.[174] To promote this belief, he wrote a theological treatise synthesizing Mexican nationalism and Book of Mormon content, published in 1935. Anglo-American LDS Church leadership suppressed the book and eventually excommunicated Bautista, and he went on to found a new Mormon denomination. Officially named El Reino de Dios en su Plenitud, the denomination continues to exist in Colonial Industrial, Ozumba, Mexico as a church with several hundred members who call themselves Mormons.[173]

Separate editions of the Book of Mormon have been published by a number of churches in the Latter Day Saint movement,[175] along with private individuals and organizations not endorsed by any specific denomination.[176]

Historicity

[edit]Mainstream views

[edit]Mainstream archaeological, historical, and scientific communities do not consider the Book of Mormon an ancient record of actual historical events.[177] Principally, the content of the Book of Mormon does not correlate with archaeological, genetic, or linguistic evidence about the past of the Americas or ancient Near East.

Archaeology

[edit]There is no accepted correlation between locations described in the Book of Mormon and known American archaeological sites.[178] Additionally, the Book of Mormon's narrative refers to the presence of animals, plants, metals, and technologies of which archaeological and scientific studies have found little or no evidence in post-Pleistocene, pre-Columbian America.[179] Such anachronistic references include crops such as barley, wheat, and silk; livestock like cattle, donkeys, horses, oxen, and sheep; and metals and technology such as brass, steel, the wheel, and chariots.[180]

Mesoamerica is the preferred setting for the Book of Mormon among many apologists who advocate a limited geography model of Book of Mormon events.[181] However, there is no evidence accepted by non-Mormons in Mesoamerican societies of cultural influence from anything described in the Book of Mormon.[182]

Genetics

[edit]Until the late-twentieth century, most adherents of the Latter Day Saint movement who affirmed Book of Mormon historicity believed the people described in the Book of Mormon text were the exclusive ancestors of all Indigenous peoples in the Americas.[183] DNA evidence proved that to be impossible, as no DNA evidence links any Native American group to ancestry from the ancient Near East as a belief in Book of Mormon peoples as the exclusive ancestors of Indigenous Americans would require. Instead, detailed genetic research indicates that Indigenous Americans' ancestry traces back to Asia,[184] and reveals numerous details about the movements and settlements of ancient Americans which are either lacking in, or contradicted by, the Book of Mormon narrative.[185][a]

Linguistics and intertextuality

[edit]There are no widely accepted linguistic connections between any Native American languages and Near Eastern languages, and "the diversity of Native American languages could not have developed from a single origin in the time frame" that would be necessary to validate a hemispheric view of Book of Mormon historicity.[200] The Book of Mormon states it was written in a language called "Reformed Egyptian", clashing with Book of Mormon peoples' purported origin as the descendants of a family from the Kingdom of Judah, where inhabitants would have communicated in Aramaic, not Egyptian.[201] There are no known examples of "Reformed Egyptian".[202]

The Book of Mormon also includes excerpts from and demonstrates intertextuality with portions of the biblical Book of Isaiah whose widely accepted periods of creation postdate the alleged departure of Lehi's family from Jerusalem circa 600 BCE.[203] No Latter-day Saint arguments for a unified Isaiah or criticisms of the Deutero-Isaiah and Trito-Isaiah understandings have matched the extent of scholarship supporting later datings for authorship.[204]

Latter Day Saint views

[edit]Most adherents of the Latter Day Saint movement consider the Book of Mormon to be historically authentic and to describe events that genuinely took place in the ancient Americas.[205] Within the Latter Day Saint movement there are several individuals and apologetic organizations, most of whom are or which are composed of lay Latter-day Saints, that seek to answer challenges to or advocate for Book of Mormon historicity.[206] For example, in response to linguistics and genetics rendering long-popular hemispheric models of Book of Mormon geography impossible,[b] many apologists posit Book of Mormon peoples could have dwelled in a limited geographical region while Indigenous peoples of other descents occupied the rest of the Americas.[208] To account for anachronisms, apologists often suggest Smith's translation assigned familiar terms to unfamiliar ideas.[209] In the context of a miraculously translated Book of Mormon, supporters affirm that anachronistic intertextuality may also have miraculous explanations.[210]

Some apologists strive to identify parallels between the Book of Mormon and biblical antiquity, such as the presence of several complex chiasmi resembling a literary form used in ancient Hebrew poetry and in the Old Testament.[211] Others attempt to identify parallels between Mesoamerican archaeological sites and locations described in the Book of Mormon, such as John L. Sorenson, according to whom the Santa Rosa archaeological site resembles the city of Zarahemla in the Book of Mormon.[212] When mainstream, non-Mormon scholars examine alleged parallels between the Book of Mormon and the ancient world, however, scholars typically deem them "chance based upon only superficial similarities" or "parallelomania", the result of having predetermined ideas about the subject.[213]

Despite the popularity and influence among Latter-day Saints of literature propounding Book of Mormon historicity,[214] not all Mormons who affirm Book of Mormon historicity are universally persuaded by apologetic work.[215] Some claim historicity more modestly, such as Richard Bushman's statement that "I read the Book of Mormon as informed Christians read the Bible. As I read, I know the arguments against the book's historicity, but I can't help feeling that the words are true and the events happened. I believe it in the face of many questions."[216]

Some denominations and adherents of the Latter Day Saint movement consider the Book of Mormon a work of inspired fiction[162] akin to pseudepigrapha or biblical midrash that constitutes scripture by revealing true doctrine about God, similar to a common interpretation of the biblical Book of Job.[217] Many in Community of Christ hold this view, and the leadership takes no official position on Book of Mormon historicity; among lay members, views vary.[218] Some Latter-day Saints consider the Book of Mormon fictional, although this view is marginal in the denomination at large.[219]

Beliefs about geographical setting

[edit]Related to the work's historicity is consideration of where its events are claimed to have occurred if historical. The LDS Church—the largest denomination in the Latter Day Saint movement[220]—affirms the book as literally historical but does not make a formal claim of where precisely its events took place.[221] Throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries, Joseph Smith and others in the Latter Day Saint movement claimed that the book's events occurred broadly throughout North and South America.[182] During the twentieth century, Latter-day Saint apologists backed away from this hemispheric belief in favor of believing the book's events took place in a more limited geographic setting within the Americas.[200] This limited geography model gained broader currency in the LDS Church in the 1990s,[222] and in the twenty-first century it is the most popular belief about Book of Mormon geography among those who believe it is historical.[223] In 2006, the LDS Church revised its introduction to LDS editions of the Book of Mormon, which previously read that Lamanites were "the principal ancestors of the American Indians", to read that they are "among the ancestors of the American Indians".[224][225] A movement among Latter-day Saints called Heartlanders believes that the Book of Mormon took place specifically within what is presently the United States.[226]

Historical context

[edit]American Indian origins

[edit]Contact with the Indigenous peoples of the Americas prompted intellectual and theological controversy among many Europeans and European Americans who wondered how biblical narratives of world history could account for hitherto unrecognized Indigenous societies.[227] From the seventeenth century through the early nineteenth, numerous European and American writers proposed that ancient Jews, perhaps through the Lost Ten Tribes, were the ancestors of Native Americans.[228] One of the first books to suggest that Native Americans descended from Jews was written by Jewish-Dutch rabbi and scholar Manasseh ben Israel in 1650.[229] Such curiosity and speculation about Indigenous origins persisted in the United States into the antebellum period when the Book of Mormon was published,[230] as archaeologist Stephen Williams explains that "relating the American Indians to the Lost Tribes of Israel was supported by many" at the time of the book's production and publication.[231] Although the Book of Mormon did not explicitly identify Native Americans as descendants of the diasporic Israelites in its narrative, nineteenth-century readers consistently drew that conclusion and considered the book theological support for believing American Indians were of Israelite descent.[232]

European descended settlers took note of earthworks left behind by the Mound Builder cultures and had some difficulty believing that Native Americans, denigrated in racist colonial worldviews and whose numbers had been greatly reduced over the previous centuries, could have produced them. A common theory was that a more "civilized" and "advanced" people had built them, but were overrun and destroyed by a more savage, numerous group.[233] Some Book of Mormon content resembles this "mound-builder" genre pervasive in the nineteenth century.[234][235][236] Historian Curtis Dahl wrote, "Undoubtedly the most famous and certainly the most influential of all Mound-Builder literature is the Book of Mormon (1830). Whether one wishes to accept it as divinely inspired or the work of Joseph Smith, it fits exactly into the tradition."[237] Historian Richard Bushman argues the Book of Mormon does not comfortably fit the Mound Builder genre because contemporaneous writings that speculated about Native origins "were explicit about recognizable Indian practices"[c] whereas the "Book of Mormon deposited its people on some unknown shore—not even definitely identified as America—and had them live out their history" without including tropes that Euro-Americans stereotyped as Indigenous.[238]

Critique of the United States

[edit]This article may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (June 2024) |

The Book of Mormon can be read as a critique of the United States during Smith's lifetime. Historian of religion Nathan O. Hatch called the Book of Mormon "a document of profound social protest",[239] and historian Bushman "found the book thundering no to the state of the world in Joseph Smith's time."[240] In the Jacksonian era of antebellum America, class inequality was a major concern as fiscal downturns and the economy's transition from guild-based artisanship to private business sharpened economic inequality, and poll taxes in New York limited access to the vote, and the culture of civil discourse and mores surrounding liberty allowed social elites to ignore and delegitimize populist participation in public discourse.[citation needed] Against the backdrop of these trends, the Book of Mormon condemned upper class wealth as elitist,[239] and it criticized social norms around public discourse that silenced critique of the country.[citation needed]

Manuscripts

[edit]

Joseph Smith dictated the Book of Mormon to several scribes over a period of 13 months,[241] resulting in three manuscripts. Upon examination of pertinent historical records, the book appears to have been dictated over the course of 57 to 63 days within the 13-month period.[242]

The 116 lost pages contained the first portion of the Book of Lehi; it was lost after Smith loaned the original, uncopied manuscript to Martin Harris.[47]

The first completed manuscript, called the original manuscript, was completed using a variety of scribes. Portions of the original manuscript were also used for typesetting.[243][better source needed] In October 1841, the entire original manuscript was placed into the cornerstone of the Nauvoo House, and sealed up until nearly forty years later when the cornerstone was reopened. It was then discovered that much of the original manuscript had been destroyed by water seepage and mold. Surviving manuscript pages were handed out to various families and individuals in the 1880s.[244]

Only 28 percent of the original manuscript now survives, including a remarkable find of fragments from 58 pages in 1991. The majority of what remains of the original manuscript is now kept in the LDS Church's archives.[243][better source needed]

The second completed manuscript, called the printer's manuscript, was a copy of the original manuscript produced by Oliver Cowdery and two other scribes.[243][better source needed] It is at this point that initial copyediting of the Book of Mormon was completed. Observations of the original manuscript show little evidence of corrections to the text.[244] Shortly before his death in 1850, Cowdery gave the printer's manuscript to David Whitmer, another of the Three Witnesses. In 1903, the manuscript was bought from Whitmer's grandson by the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, now known as the Community of Christ.[245] On September 20, 2017, the LDS Church purchased the manuscript from the Community of Christ at a reported price of $35 million.[246] The printer's manuscript is now the earliest surviving complete copy of the Book of Mormon.[247] The manuscript was imaged in 1923 and has been made available for viewing online.[248]

Critical comparisons between surviving portions of the manuscripts show an average of two to three changes per page from the original manuscript to the printer's manuscript.[243][better source needed] The printer's manuscript was further edited, adding paragraphing and punctuation to the first third of the text.[243][better source needed]

The printer's manuscript was not used fully in the typesetting of the 1830 version of Book of Mormon; portions of the original manuscript were also used for typesetting. The original manuscript was used by Smith to further correct errors printed in the 1830 and 1837 versions of the Book of Mormon for the 1840 printing of the book.[243][better source needed]

Printer's manuscript ownership history

[edit]In the late-19th century the extant portion of the printer's manuscript remained with the family of David Whitmer, who had been a principal founder of the Latter Day Saints and who, by the 1870s, led the Church of Christ (Whitmerite). During the 1870s, according to the Chicago Tribune, the LDS Church unsuccessfully attempted to buy it from Whitmer for a record price. Church president Joseph F. Smith refuted this assertion in a 1901 letter, believing such a manuscript "possesses no value whatever."[249] In 1895, Whitmer's grandson George Schweich inherited the manuscript. By 1903, Schweich had mortgaged the manuscript for $1,800 and, needing to raise at least that sum, sold a collection including 72 percent of the book of the original printer's manuscript (John Whitmer's manuscript history, parts of Joseph Smith's translation of the Bible, manuscript copies of several revelations, and a piece of paper containing copied Book of Mormon characters) to the RLDS Church (now the Community of Christ) for $2,450, with $2,300 of this amount for the printer's manuscript.

In 2015, this remaining portion was published by the Church Historian's Press in its Joseph Smith Papers series, in Volume Three of "Revelations and Translations"; and, in 2017, the church bought the printer's manuscript for US$35,000,000.[250]

Editions

[edit]Chapter and verse notation systems

[edit]The original 1830 publication had no verses (breaking the text into paragraphs instead). The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' (LDS Church) 1852 edition numbered the paragraphs.[251] Orson Pratt, an apostle of the denomination, divided the text into shorter chapters, organized it into verses, and added paratextual footnotes.[252] In 1920, the LDS Church published a new edition edited by apostle James E. Talmage, who reformatted the text into double columns, imitating the prevailing format of Bibles in the United States.[253] The next new Latter-day saint edition of the book was published in 1981; this edition added new chapter summaries and cross references.[254]

The Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS Church; later renamed to Community of Christ) also published editions of the Book of Mormon.[255] It printed editions at Plano, Illinois and Lamoni, Iowa in 1874.[256] In 1892, the church published a large-print edition that split the original edition's paragraphs into shorter ones.[257] From 1906 to 1908, Reversification Committee appointed by the RLDS Church revised its Book of Mormon text based on manuscript comparison and also reformatted it into shorter verses (though it retained the original chapter lengths); the RLDS Church published this version as the Revised Authorized edition, printing it beginning in April 1909.[258]

Church editions

[edit]| Publisher | Year | Titles and notes | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints | 1981 | The Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ.[259] New introductions, chapter summaries, and footnotes. 1920 edition errors corrected based on original manuscript and 1840 edition.[251] Updated in a revised edition in 2013.[260][261] | link |

| Community of Christ | 1966 | "Revised Authorized Version", based on 1908 Authorized Version, 1837 edition and original manuscript.[262] Omits numerous repetitive "it came to pass" phrases. | |

| The Church of Jesus Christ (Bickertonite) | 2001 | Compiled by a committee of Apostles. It uses the chapter and verse designations from the 1879 LDS edition.[citation needed] | |

| Church of Christ with the Elijah Message | 1957 | The Record of the Nephites, "Restored Palmyra Edition". 1830 text with the 1879 LDS edition's chapters and verses. | link |

| Church of Christ (Temple Lot) | 1990 | Based on 1908 RLDS edition, 1830 edition, printer's manuscript, and corrections by church leaders. | link |

| Fellowships of the remnants | 2019 | Based on Joseph Smith's last personally-updated 1840 version, with revisions per Denver Snuffer Jr.[263] Distributed jointly with the New Testament, in a volume called the "New Covenants". | link |

Other editions

[edit]| Publisher | Year | Titles and notes | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| Herald Heritage | 1970 | Facsimile of the 1830 edition.[citation needed] | |

| Macmillan | 1992 | Encyclopedia of Mormonism. The Encyclopedia's fifth volume includes the full text of the Book of Mormon, as well as the Doctrine and Covenants and Pearl of Great Price.[264] There are brief introductions but no footnotes or indices (an index to the Encyclopedia is found in its fourth volume).[265] The Encyclopedia, including the volume containing the Book of Mormon, is no longer in print.[266] | |

| Zarahemla Research Foundation | 1999 | The Book of Mormon: Restored Covenant Edition. Text from Original and Printer's Manuscripts, in poetic layout.[267] | link Archived May 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine |

| Bookcraft | 1999 | The Book of Mormon for Latter-day Saint Families. Large print with visuals and explanatory notes.[268] | |

| University of Illinois Press | 2003 | The Book of Mormon: A Reader's Edition. The text of the 1920 LDS edition reformatted into paragraphs and poetic stanzas and accompanied by some footnotes.[269] | link |

| Doubleday | 2004 | The Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ. Text from the LDS edition without footnotes.[270] A second edition was printed in 2006.[271] | link |

| Signature Books | 2008 | The Reader's Book of Mormon. Text from the 1830 edition with its original paragraphing and without versification. Published in seven volumes, each introduced with a personal essay on the portion of the Book of Mormon contained.[272] | |

| Penguin Books | 2008 | The Book of Mormon. Penguin Classics series. Paperback with 1840 text,[272] "the last edition that Smith himself edited."[273] | link |

| Yale University Press | 2009 | The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text. Joseph Smith's dictated text with corrections from Royal Skousen's study of more than five thousand textual variances across manuscripts and editions.[274] | link |

| The Olive Leaf Foundation | 2017 | A New Approach To Studying The Book Of Mormon. The complete text of the 1981 edition organized in paragraphs and poetic stanzas, annotated with marginal notes, and divided into event-based chaptering.[275] | link |

| Neal A. Maxwell Institute | 2018 | The Book of Mormon: Another Testament of Jesus Christ, Maxwell Institute Study Edition. Text from the church's 1981 and 2013 editions reformatted into paragraphs and poetic stanzas. Selected textual variants discovered in the Book of Mormon Critical Text Project appear in footnotes.[276] | |

| Digital Legend Press | 2018 | Annotated Edition of the Book of Mormon. Text from the 1920 edition footnoted and organized in paragraphs.[277] |

Historic editions

[edit]The following editions no longer in publication marked major developments in the text or reader's helps printed in the Book of Mormon.

| Publisher | Year | Titles and notes | Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. B. Grandin | 1830 | "First edition" in Palmyra. Based on printer's manuscript copied from original manuscript. | link |

| Pratt and Goodson | 1837 | "Second edition" in Kirtland. Revision of first edition, using the printer's manuscript with emendations and grammatical corrections.[251] | link |

| Ebenezer Robinson and Smith | 1840 | "Third edition" in Nauvoo. Revised by Joseph Smith[273] in comparison to the original manuscript.[251] | link |

| Young, Kimball and Pratt | 1841 | "First European edition". 1837 reprint with British spellings.[251] Future LDS editions descended from this, not the 1840 edition.[278] | link |

| Joseph Smith Jr. | 1842 | "Fourth American edition" in Nauvoo. A reprint of the 1840 edition. Facsimiles of an original 1842 edition. | |

| Franklin D. Richards | 1852 | "Third European edition". Edited by Richards. Introduced primitive verses (numbered paragraphs).[251] | link |

| James O. Wright | 1858 | Unauthorized reprinting of 1840 edition. Used by the early RLDS Church in 1860s.[251] | link |

| Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | 1874 | First RLDS edition. 1840 text with verses.[251] | link |

| Deseret News | 1879 | Edited by Orson Pratt. Introduced footnotes, new verses, and shorter chapters.[251] | link |

| Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints | 1908 | "Authorized Version". New verses and corrections based on printer's manuscript.[251] | link |

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints | 1920 | Edited by James E. Talmage. Added introductions, double columns, chapter summaries, new footnotes,[251] pronunciation guide.[279] | link |

Non-English translations

[edit]

The Latter-day Saints version of the Book of Mormon has been translated into 83 languages and selections have been translated into an additional 25 languages. In 2001, the LDS Church reported that all or part of the Book of Mormon was available in the native language of 99 percent of Latter-day Saints and 87 percent of the world's total population.[280]

Translations into languages without a tradition of writing (e.g., Kaqchikel, Tzotzil) have been published as audio recordings and as transliterations with Latin characters.[281] Translations into American Sign Language are available as video recordings.[282][283][284]

Typically, translators are Latter-day Saints who are employed by the church and translate the text from the original English. Each manuscript is reviewed several times before it is approved and published.[285]

In 1998, the church stopped translating selections from the Book of Mormon and announced that instead each new translation it approves will be a full edition.[285]

Representations in media

[edit]

Artists have depicted Book of Mormon scenes and figures in visual art since the beginnings of the Latter Day Saint movement.[286] The nonprofit Book of Mormon Art Catalog documents the existence of at least 2,500 visual depictions of Book of Mormon content.[287] According to art historian Jenny Champoux, early artwork of the Book of Mormon relied on European iconography; eventually, a distinctive "Latter-day Saint style" developed.[286]

Events of the Book of Mormon are the focus of several films produced by the LDS Church, including The Life of Nephi (1915),[288] How Rare a Possession (1987) and The Testaments of One Fold and One Shepherd (2000).[289] Depictions of Book of Mormon narratives in films not officially commissioned by the church (sometimes colloquially known as Mormon cinema) include The Book of Mormon Movie, Vol. 1: The Journey (2003) and Passage to Zarahemla (2007).[290]

In "one of the most complex uses of Mormonism in cinema," Alfred Hitchcock's film Family Plot portrays a funeral service in which a priest (apparently non-Mormon, by his appearance) reads Second Nephi 9:20–27, a passage describing Jesus Christ having victory over death.[289]

In 2011, a long-running satirical musical titled The Book of Mormon, written by South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone in collaboration with Robert Lopez, premiered on Broadway, winning nine Tony Awards, including Best Musical.[291] Its London production won the Olivier Award for best musical. The musical is not principally about Book of Mormon content and tells an original story about Latter-day Saint missionaries in the twenty-first century.[292]

In 2019, the church began producing a series of live-action adaptations of various stories within the Book of Mormon, titled Book of Mormon Videos, which it distributed on its website and YouTube channel.[293][294]

See also

[edit]- Journal of Book of Mormon Studies

- List of Gospels

- Studies of the Book of Mormon

- List of Book of Mormon places

- Pre-Columbian transoceanic contact theories

- Book of Mormon Videos

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ The first settlers in the Americas were Paleolithic hunter-gatherers (Paleo-Indians) who entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum.[186] These populations expanded south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet and spread rapidly southward, occupying both North and South America, by 12,000 to 14,000 years ago.[187][188][189][190][191] Indigenous peoples of the Americas have been linked to Siberian populations by genetic composition as reflected by molecular data, such as DNA.[192][193] Analyses of genetics among Indigenous American and Siberian populations have been used to argue for early isolation of founding populations on Beringia[194] and for later, more rapid migration from Siberia through Beringia into the New World.[195] The microsatellite diversity and distributions of the Y lineage specific to South America indicates that certain Indigenous American populations have been isolated since the initial peopling of the region.[196] The Na-Dene, Inuit and Native Alaskan populations exhibit Haplogroup Q-M242; however, they are distinct from other Indigenous Americans with various mtDNA and atDNA mutations.[197] This suggests that the peoples who first settled in the northern extremes of North America and Greenland derived from later migrant populations than those who penetrated farther south in the Americas.[198][199]

- ^ The "hemispheric model" refers to a belief that the Book of Mormon's setting spanned North and South America and that Indigenous peoples of the Americas principally descended from Book of Mormon peoples.[183] Linguistically, the diversity of Native American languages that exists could not have developed in the time frame required by Lehi's arrivants being the sole ancestors of Indigenous peoples in the Americas.[200] Genetically, DNA evidence links the Indigenous peoples of the Americas to Asia.[207]

- ^ For example, Abner Cole's parody of the Book of Mormon, The Book of Pukei, described characters wearing moccasins.[238]

Citations

[edit]- ^ The Book of Mormon: An Account Written by the Hand of Mormon, Upon Plates Taken from the Plates of Nephi (1830 edition). E. B. Grandin. 1830.

- ^ Hardy 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Hardy 2010, pp. xi–xiii, 6.

- ^ Archives, Church News (17 August 2013). "'Keystone of our religion'". Church News. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ "The Book of Mormon is the Keystone of Our Religion". Preach My Gospel. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ Southerton 2004, p. xv. "Anthropologists and archaeologists, including some Mormons and former Mormons, have discovered little to support the existence of [Book of Mormon] civilizations. Over a period of 150 years, as scholars have seriously studied Native American cultures and prehistory, evidence of a Christian civilization in the Americas has eluded the specialists... These [Mesoamerican] cultures lack any trace of Hebrew or Egyptian writing, metallurgy, or the Old World domesticated animals and plants described in the Book of Mormon."

- ^ E.g. 2 Nephi 2

- ^ E.g. 2 Nephi 9

- ^ E.g. Alma 12

- ^ a b Hardy, Grant (2016). "Understanding Understanding the Book of Mormon with Grant Hardy". Journal of the Book of Mormon and Other Restoration Scripture (Interview). Vol. 25. Interviewed by Blair Hodges.

- ^ a b c Hardy 2010, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Translations of the Book of Mormon at LDS365.com

- ^ Givens 2009, pp. 6–11.

- ^ a b Hardy 2010, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Hales, Brian C. (2019). "Naturalistic Explanations of the Origin of the Book of Mormon: A Longitudinal Study" (PDF). BYU Studies Quarterly. 58 (3): 105–148. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Givens 2002, pp. 162–168.

- ^ Taves 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Remini 2002, pp. 43–45.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Remini 2002, p. 47.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Davis 2020, pp. 165–168.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 59, 62–63.

- ^ The materiality of the plates Smith said he translated from has long been a matter of controversy in historical studies of Smith and the Book of Mormon. Those who for religious reasons accept Smith's account of the book as having miraculous and ancient origins by corollary also have tended to believe there were authentic, ancient plates. Meanwhile, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, naturalistic interpretations of Smith's history and the Book of Mormon generally took for granted the plates had no material existence and were fictitious due to either delusion or deception, or otherwise existed only in the religious imaginary. However, "believing historians" have argued that the documentary evidence points to Smith and eyewitnesses to him consistently behaving as though he did possess material plates. Religious studies scholar Ann Taves summarizes, "that there were no actual golden plates... is so obvious to some historians that they are taken aback when they discover that many Mormon intellectuals believe there were", while "Many believing historians... in turn wonder how well-trained, non-believing historians can dismiss so much evidence" (2). In the twenty-first century, naturalistic interpretations have posited that the plates were materially real, but that Smith crafted them himself (possibly out of tin or copper), either to match his vision of the plates or after being inspired by seeing copper stereotyped printing plates (perhaps at a printing shop or, by happenstance, literally buried in the ground). Taves argues Smith nevertheless believed the plates constituted an authentic, ancient record and that crafting plates himself "can be understood as representing or even co-creating the reality of the plates... the way Eucharistic wafers are thought to be transformed into the literal body of Christ" (9). For this historiography and an argument that Smith crafted the plates in a process of materialization, see Taves (2014, pp. 1–11). For another view on this historiography and an argument that an encounter with printing plates inspired or shaped Smith's concept of the Book of Mormon plates, see Hazard, Sonia (Summer 2021). "How Joseph Smith Encountered Printing Plates and Founded Mormonism". Religion & American Culture. 31 (2): 137–192. doi:10.1017/rac.2021.11. S2CID 237394042.

- ^ Bushman 2005, p. 44.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 316. "Many people shared [a supernatural] culture, among them some jealous neighbors who tried to steal Smith's golden plates."

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Emma Smith, Reuben Hale, Martin Harris, Oliver Cowdery, and John and Christian Whitmer all scribed for Joseph Smith to varying extents. Emma Smith likely scribed the majority of the early manuscript pages that were lost and never reproduced; Harris scribed about a third. Cowdery scribed the majority of the manuscript for the Book of Mormon as it was published and exists today. See Easton-Flake & Cope (2020, p. 129); Welch (2018, pp. 17–19); Bushman (2005, pp. 66, 71–74).

- ^ Remini 2002, pp. 59–65.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 63–80.

- ^ a b Welch, John W. (2018). "Timing the Translation of the Book of Mormon: 'Days [and Hours] Never to Be Forgotten'" (PDF). BYU Studies Quarterly. 57 (4): 10–50. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- ^ Remini 2002, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Bushman 2005, p. 72.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Joseph Smith may have developed this dictation process with Emma Smith, who was his first long-term scribe. See Easton-Flake & Cope 2020, pp. 129–132.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 66, 71–72.

- ^ Howe 2007, p. 313.

- ^ Dirkmaat, Gerrit J.; MacKay, Michael Hubbard (2015). "Firsthand Witness Accounts of the Translation Process". In Largey, Dennis L.; Hedges, Andrew H.; Hilton, John III; Hull, Kerry (eds.). The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder. Religious Studies Center. pp. 61–79. ISBN 9781629721149.

- ^ a b Givens 2002, p. 34.

- ^ Hardy 2020, p. 209.

- ^ Interpretations of accounts purporting to describe what Smith saw in his seer stone (or in the Urim and Thummim) vary. Many share some basic characteristics centering around reading words which miraculously appear, such as Jesee Knight's account: "Now the way he translated was he put the urim and thummim into his hat and Darkned his Eyes then he would take a sentance and it would appear in Brite Roman Letters. Then he would tell the writer and he would write it. Then that would go away the next sentance would Come and so on." See Bushman (2005, p. 72) for Knight's account and Hardy (2020, pp. 209–210) for an interpretation arguing for this understanding of Smith's experience. Hardy contends understanding Smith reading a text best accounts for the documentary evidence of how he dictated and how his scribes wrote. Nevertheless, scholar Ann Taves points out that although such accounts share major characteristics, they are not fully consistent with each other. She hypothesizes "observers made inferences about what Smith was experiencing based on what they saw, what they learned from discussion with Smith, what they believed, or some combination thereof" and that accounts of what Smith did or did not see as he dictated do not necessarily describe Smith's experience (emphasis added). See Taves (2020, p. 177) In light of this, other scholars have hypothesized Smith's ecstatic experience as a translator was more like "panoramic visions" than reading, which he then orally described to his scribes. See Brown (2020, p. 146).

- ^ Remini 2002, p. 62.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 66, 71. "When Martin Harris had taken dictation from Joseph, they at first hung a blanket between them to prevent Harris from inadvertently catching a glimpse of the plates, which were open on a table in the room."

- ^ Bushman 2005, p. 71. "When Cowdrey took up the job of scribe, he and Joseph translated in the same room where Emma was working. Joseph looked in the seerstone, and the plates lay covered on the table."

- ^ Sweat, Anthony (2015). "The Role of Art in Teaching Latter-day Saint History and Doctrine". Religious Educator. 16: 40–57.

- ^ Taves 2014, p. 5.

- ^ a b Harris's wife Lucy Harris was long popularly thought to have stolen the pages. See Givens (2002, p. 33). Historian Don Bradley contests that this was a rumor that circulated only in retrospect. See Bradley (2019, pp. 58–80).

- ^ Remini 2002, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Bushman 2005, p. 68.

- ^ Remini 2002, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Bushman 2005, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Bushman 2005, p. 76. During this time, John Whitmer did some transcription, though Cowdery still performed the majority.

- ^ Bushman 2007, pp. 77–79.

- ^ a b Hardy 2003, p. 631.

- ^ Sweat, Anthony (2015). "Hefted and Handled: Tangible Interactions with Book of Mormon Objects". In Largey, Dennis L.; Hedges, Andrew H.; Hilton, John III; Hull, Kerry (eds.). The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder. Religious Studies Center, Deseret Book. pp. 43–59. ISBN 9781629721149. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021.

- ^ Hazard, Sonia (Summer 2021). "How Joseph Smith Encountered Printing Plates and Founded Mormonism". Religion & American Culture. 31 (2): 137–192. doi:10.1017/rac.2021.11. S2CID 237394042.

- ^ Bushman, Richard (August 22, 2020). "Richard Bushman on the Gold Plates". From the Desk (Interview). Interviewed by Kurt Manwaring. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021.

- ^ Kunz, Ryan (March 2010). "180 Years Later, Book of Mormon Nears 150 Million Copies". Ensign: 74–76. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ^ Remini 2002, p. 68.